The Active Equity Renaissance: Rejecting a Broken 1970s Model

Posted by Jason Apollo Voss on Mar 14, 2017 in Active Equity Renaissance, Best of the Blog, Blog | 0 commentsThe average active equity mutual fund underperforms its benchmark.

This statement sparks little controversy and can be applied to active equity hedge funds as well.

The story gets worse when the results are AUM-weighted. Collectively, active equity delivers no value to its investors and, in fact, extracts value from them.

In our highly competitive markets, what industry can survive if it fails to deliver value to its customers? The consequences of these competitive forces are clear as money flows out of active and into passive equity funds. Passive investing is being touted as the superior alternative, and who can argue?

As an active equity industry, we have to ask ourselves how we descended into such a sorry state. The conventional explanation is that portfolio managers and their investment teams lack stock-picking skill. But as is often the case, the answer is not so simple.

A more careful analysis indicates that investment teams, buy-side analysts in particular, are not the problem. Instead, the fund distribution system is what’s at fault.

So rather than loudly denouncing the lack of stock-picking skills, those in the distribution system have some soul searching to do. As Pogo used to say: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Buy-Side Analysts Are Superior Stock Pickers

There is considerable research showing that buy-side analysts are superior stock pickers. I conducted a study that supports this conclusion.

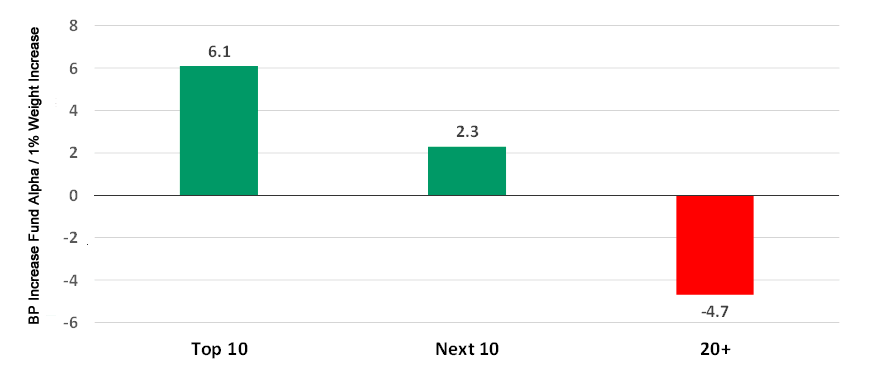

Active Equity Fund Best Ideas: Top 20 Relative-Weight Stocks*

* Based on single variable, subsequent gross fund alpha regressions estimated using a data set of 44 million stock-month US active equity mutual fund holdings from January 2001 to September 2014. Source: Lipper and Morningstar

The top 20 relative-weight holdings generate fund alpha, while the low-ranked holdings destroy it. So any restriction imposed on a fund that mandates holding anything other than the best idea stocks negatively affects a fund’s alpha. If enough mandates are added, a potential positive alpha is transformed into an actual negative alpha.

The fund distribution system is full of such restrictions: Fund managers are required to hold many stocks for diversification purposes, manage to low volatility and drawdown, avoid tracking error and style drift, grow large, and impose sector-weighting constraints.

In essence, the distribution system is a closet indexer manufacturing juggernaut.

To be clear, we are talking about those who run the distribution system, both inside and outside the fund. The internal sales and marketing teams work hand in glove with the external platforms — broker-dealers, registered investment advisers (RIAs), and institutional investors — imposing value-destroying restrictions on investment teams.

The “pot of gold” generated by an analyst’s investment decisions — somewhere around a 4% average alpha based on several studies — is eaten up by fund fees and the external restrictions placed on the fund.

In the end, the fund itself captures the entire potential alpha and then some by growing too large, ultimately turning itself into a closet indexer. None of the alpha is delivered outside the fund, and worse, additional value is extracted from investors.

Fixing a Broken Investment Management Model

A system that encourages closet indexing while delivering negative value to investors is clearly broken. So what is to be done?

Investment teams, particularly buy-side analysts, need to be elevated to a starring role since they deliver the most value to investors. Funds need to be rewarded for consistently pursuing a narrowly defined strategy, taking only high-conviction positions.

Participants in the distribution system need to avoid imposing restrictions that impede the successful pursuit of an equity strategy. More specifically, asset bloat, benchmark tracking, and over-diversification need to be discouraged. Why? Because these are the precursors to closet indexing.

To resurrect the industry, an important first step is to move away from the discredited 1970s modern portfolio theory (MPT). Not only is the evidence overwhelmingly against this model, but MPT provides the theoretical justification for many of the value-destroying restrictions foisted upon funds.

The new market paradigm will most likely arise from behavioral finance. The discipline is already transforming the advisory business. Major players — Merrill Lynch and Morningstar, among others — have established behavioral finance units and are disseminating the resulting research throughout the adviser community.

This is an important value add in the competition with robo-advisers. The mechanical solution offers little help in steering investors away from value-destroying emotional errors. Studies reveal that focusing on minimizing emotional investing can enhance returns by 2%–4%.

Some financial advisers now think of themselves as behavioral advisers. A recent sign of this industry trend: the Behavioral Financial Advisor certification and designation.

Can a “Behavioral Financial Analyst” be far behind? Behaviorally based objective measures will begin to replace the metrics currently used to analyze investments. Several of these measures — asset bloat, benchmark tracking, and over-diversification — are more predictive of fund underperformance. That is, objective behavioral measures are predictive, while the traditional measures targeting past performance are not.

A Robust Debate

Future posts in this series will provide suggestions on how the system might be fixed. The goal is not to present final solutions, but to spark a robust debate around the many challenges facing a broken industry.

Imagine a world in which only the lowest-cost index funds along with truly active, alpha-generating funds exist, without a closet indexer in sight.

Together let’s launch the active equity renaissance!

Image credit: ©Getty Images/duncanecampbell

Originally published on CFA Institute’s Enterprising Investor.