In a previous post, I distilled some of the valuable information about investment manager stress-coping mechanisms detailed in the Research Foundation of CFA Institute’s recent monograph, Fund Management: An Emotional Finance Perspective, authored by David Tuckett and Richard J. Taffler. This first-of-its-kind publication contains many previously unexplored emotional aspects of fund management worthy of highlighting.

In this post, I’ll review the authors’ analysis of how stories are used by investment managers to gain conviction in an investment idea — all too often with deleterious consequences. I say deleterious because, as a former fund manager, I know that there is a constant danger of being married to my “story” and the contextualization/mental framework it provides rather than orienting my mind to the facts themselves.

The authors define storytelling as the narrative that investment professionals weave around the disparate facts of a business that serve as a way of understanding a prospective investment. One example of storytelling helps illustrate (bear in mind that both the names of the interview subjects and the company in question have been changed by the authors):

“[George] related that he had some initial interest [in Fast Foods] but ‘didn’t know enough as to what was going on with the name.’ It was not, he thought, ‘an easy company to see’ through. So, he went to a company meeting to learn more: ‘They had a meeting at their headquarters.’ And when he met the management, he quickly formed the impression that ‘they really try to focus on managing their business’, and he was impressed. ‘I said, “Oh my goodness, I think I like what I’m hearing.’

Back in his office the next day, he began ‘pushing the numbers . . . I came up with a number that was 10% higher than consensus street estimates’, he said, and he believed ‘it could go even more . . . if this new product line . . . then it’s even better’. On top of these beliefs was an ‘international kicker’ — in other words, they were expanding globally. Also, George Monroe was delighted that ‘they really kept talking about monitoring risk and measuring risk and getting risk out of the business model’. This approach made him feel secure: ‘Now, other people don’t get so excited about that, but I say, “Oh, they’re taking risk away.” Your chance of success is so much higher.’ Monroe bought the shares. ‘It was great’, he said, ‘all of those things sort of played out in spades, like way beyond what I had imagined. . . . It’s really gone up a lot, probably 50%, and they are continuing to execute just incredibly well. I think this next quarter is going to be humungous.”

Tuckett and Taffler contend that these stories are one of the principle ways that investment managers arrive at a conviction in the face of overwhelming tides of information and uncertain futures. In other words, stories allow managers to feel as if the chaotic nature of the world can be managed and that there are underlying and understandable patterns that make sense.

Crucially, their findings about “stories” also demonstrate that arriving at conviction is not just a simple matter of overconfidence, as is typically suggested by the behavioral finance literature. Both Tuckett and Taffler are psychiatrists, and they say that most of the investment managers they interviewed were “rather thoughtful and modest.”

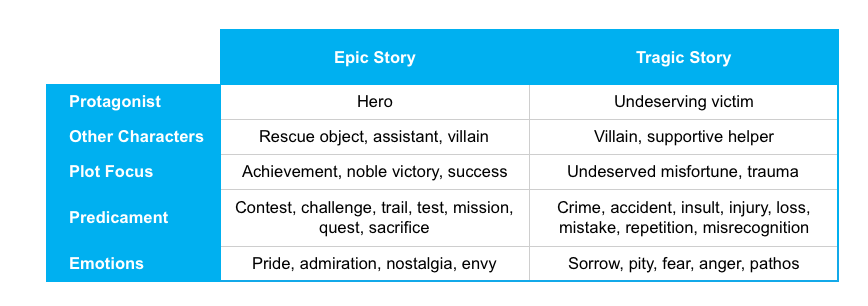

One fellow story researcher quoted by the authors is “Gabriel,” who defines stories as “narratives with plots and characters, generating emotion in narrator and audience through a poetic elaboration of symbolic material . . . [entailing] conflicts, predicaments, trials, coincidences, and crises that call for choices, decisions, [and] actions.” These stories tend to create a sense of purpose and meaning into a chain of seemingly unrelated events, and therefore help calm the anxiety of fund managers. While Gabriel identified many story types, Tuckett and Taffler focus on the two that fund managers seem to engage in the most: the “epic” and the “tragedy.”

In epic stories, the plot revolves around an important success in the face of stringent competition. Epic stories are designed to elicit pride in the narrator and admiration for the hero on the part of the listener. The epic always has a happy ending. Tragic stories, by contrast, are virtually the opposite of the epic: Their plots involve misfortune and villainy, and they are designed to evince feelings of pity or sorrow for the undeserving victim/protagonist.

Here is a summary table taken from Fund Management: An Emotional Finance Perspective:

Intimately related to storytelling are meta-narratives. These are the narratives used at investment banks and companies that distill the essence of the firms’ investment philosophies. In other words, this is the raison d’être or alpha argument about how the firm adds value for investors. For investment managers, meta-narratives allow them to perform their work.

How you may ask? When the performance of individual investments or markets does not move in favor of the investment manager, he or she is able to use the meta-narrative to remain vigilant throughout the fluctuations. An example would be the story, “We are value investors and right now the valuations are too rich,” which is offered when an investment portfolio is underperforming relative to an advancing benchmark.

So meta-narratives serve a useful function in helping investment professionals manage disappointment. Said otherwise: When markets disabuse portfolio performance, meta-narratives are not questioned because they are treated as sacrosanct. Instead, stories make sense of the bewildering array of facts and the disappointment of an investment idea gone awry.

Tuckett and Taffler find that both stories and meta-narratives are rather flexible, meaning that they are only compelling if they are not probed too deeply. Perhaps, then, the ultimate reason for stories and meta-narratives is a need to bring organization to a deeply felt need for how investment decisions are properly made, or ought to be made. In other words, investment managers want to believe that there is logic and reason underlying their work.

Photo credit: ©iStockphoto.com/MHJ

Originally published on CFA Institute’s Enterprising Investor.

0 Comments