Earlier this week we asked CFA Institute Financial NewsBrief readers: “What is the biggest sin for an active manager relative to its relationship to an investment consultant?” and 652 of you responded. Our goal is to bring clarity to a frequently strained relationship — that between investment consultants and active investment managers.

Investment Consultant Needs

On one side, you have investment consultants representing their clients’ fiduciary interests. These include a variety of outcomes, mainly appreciation of capital, but also capital preservation, income, and diversification. To deliver on these goals, consultants usually approach investment management as an investment policy and asset allocation issue.

What they require from an investment manager is not just returns vs. risks ≥ 1, but also consistency and predictability. Without those, they doubt their asset allocation strategies and investment policy statements will be accurately delivered. To ensure their desired outcome, consultants will scrutinize an active manager’s staff turnover, governance, style drift, tracking error, and performance.

Active Manager Needs

On the other side, you have active investment managers whose needs often do not overlap those of investment consultants. Active managers need freedom to create strategies that exalt, rather than stifle their capabilities, time for their strategies to bear fruit, and assets under management of a scale to support their endeavors. It is this latter goal that leads active managers to engage with investment consultants.

But is this collaboration the only way to attain that goal? If the answer is yes, then active managers are subject to the risk of committing certain fatal sins from the perspective of investment consultants.

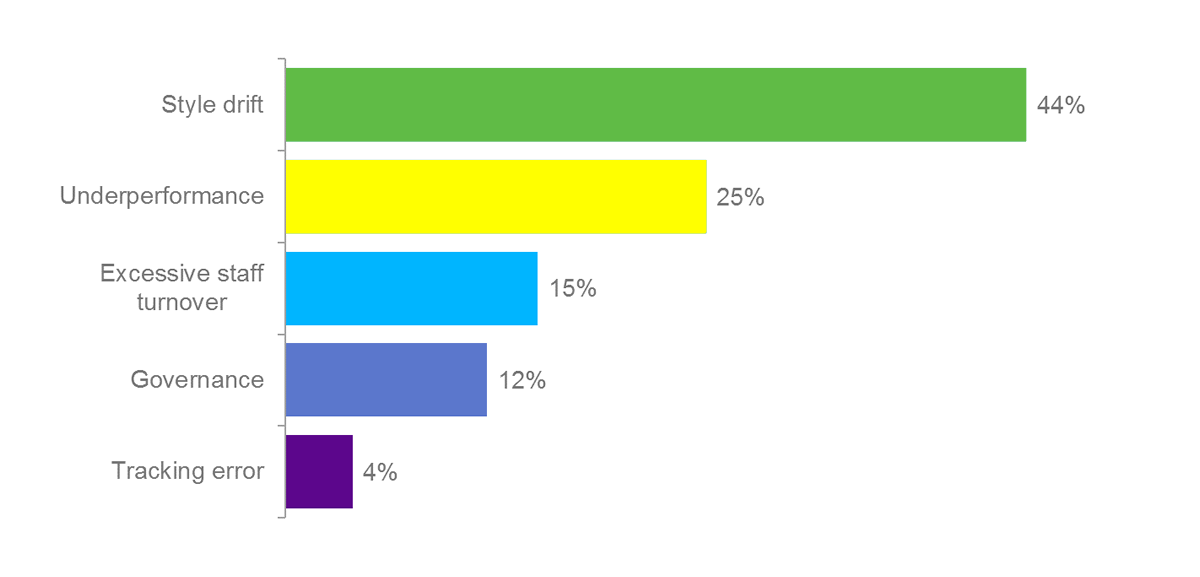

What is the biggest sin for an active manager relative to its relationship to an investment consultant?

Sins and How They Stack Up

Style Drift and Tracking Error: With 44% of the vote, the greatest sin for an active manager to commit relative to an investment consultant is style drift. Why is this a sin? Style drift occurs when a manager is hired by the consultant to deliver style-specific results, yet the actual results are more similar to those of a different style. The consequence for the investment consultant is a fouled-up asset allocation and investment policy statement — and perhaps, an upset client.

From the perspective of the active manager, style drift may be the natural outcome of a flawlessly executed style. For example, a value manager that consistently identifies undervalued securities through careful due diligence may experience capital appreciation for the entire portfolio that leads to it looking like a “growth” portfolio. Conversely, the growth manager that identifies a security whose returns outpace those of the market may see those excess returns on capital dry up as others bid up the price of the security or the issuing company experiences an economic slowdown. Here the growth manager can look like a value manager.

Also, success can lead to drift in terms of capitalization-oriented categories. So is some style drift the natural consequence of success, and not necessarily poor investment management?

In order to tell the difference, superior measures of style are needed. Yet, the investment management industry, including consultants, frequently relies upon very naive measures of style drift, such as book-to-price ratios. Here the entire universe of a benchmark, say the S&P 500, is divided into thirds. The highest book-to-price third is deemed value, the lowest third is deemed growth, and the middle, by default, is deemed core. This measure does not provide absolute standards of style because prices vary. For active managers, this means their evaluation is based on an arbitrary and moving target.

When you combine the style drift results with tracking error at 4%, you have nearly a majority who believe the greatest sin for active managers is violating the modeling expectations of investment consultants. Contrast the investment consultant’s need for stability with the active manager’s need to create strategies that exalt, rather than stifle their capabilities, as well as time for their strategies to bear fruit, and you can see a major disconnect.

Is there strong evidence that consultants’ asset allocation strategies actually deliver for their clients? More research needs to be done in order to justify shackling active investment managers with possibly flawed measures of success.

Excessive Staff Turnover: Investment consultants evaluate the stability and consistency of an investment management staff by considering the amount of turnover. Consultants prefer long tenures, and 15% of poll respondents agreed this is important.

In part, this may be due to the difficulty of precisely evaluating qualitative factors, and, consequently, the difficulty in confidently presenting to clients. Ironically though, staff turnover can be driven by both the failure and success of the active manager. If a strategy consistently fails, then assets under management typically shrink and with it bonuses, and ultimately, salaries. A high degree of success also leads investment professionals to leave their firms so they can attract assets under management for their own proprietary investment strategies, at best, or to ring up a higher bid for their research acumen, at worst.

In some ways a lack of staff turnover indicates a good culture. A high quality manager, culturally-speaking, should be able to retain talent in bad times and in good. This is the generous view of a common investment consultant measure, while the cynical view is that average staff turnover is a number, and quantities can be screened for in manager searches.

Governance: Nearly 12% of respondents believe bad governance to be the biggest sin. Risk exists any time a client turns over her capital to a financial intermediary, such as an investment consultant or active investment manager. Therefore, the trustworthiness of such parties must be evaluated. This is referred to as governance, and we evaluate not just the actions of fiduciaries, but also the structures put in place by these individuals.

Careful consideration is given to expense ratios, board structure — including the proportion of insiders to outsiders, returns calculation, portfolio composition, and transparency into the research process. Paying attention to governance makes sense for all participants in the financial industry, because transactions should take place only in a trustworthy environment.

Underperformance: Though 25% of poll respondents ranked underperformance as the biggest sin, I have saved it until last to discuss. Why? It is a little appreciated secret of investment management that performance, or underperformance, relative to expectations, is not in the control of an active manager. This is not the same thing as saying that performance is random!

Performance is an outcome, based on exceptional processes on the front end. If the processes are executed in accord with an active manager’s needs, then these managers can expect variation in their returns around an altogether different mean than active managers without exceptional process.

Another reason for saving this until last is the complex agency costs involved in the relationship among asset managers, investment consultants, and their respective clients. Both asset managers and investment consultants are hired by the same client, but both do not necessarily enjoy the same relationship with the client at a given point in time.

Investment consultants have significant input into the client’s hiring of asset managers, so clients can look to the consultant if displeased with an asset manager’s performance. Fear of disappointing clients means that consultants can quickly turn from ally to adversary.

Sometimes asset managers enjoy a strong relationship with clients, but consultants’ relationships are at risk. More often, these relationships hinge on timing. Specifically, just how short a timeframe, in terms of quarterly underperformance, do active managers have before they are fired?

Only when all three constituents agree to a time horizon is there an absence of friction. Sadly, friction frequently leads to underperformance. As managers attempt to conform to unstated expectations they often give up their inherent advantages. Anxious clients are not successfully consoled by consultants, and, in turn, consultants are not successfully consoled by active managers.

This very issue, called career risk, demands that active managers not be too active, and that they agree to be shackled by measures like style boxes, style drift, and tracking error instead. Research from two sources, Joachim Klement, and C. Thomas Howard, PhD, respectively, highlight many of these deleterious effects on active portfolio management.

The results of our poll comport well with those of the joint survey of investment professionals and clients conducted by CFA Institute and Edelman entitled, “From Trust to Loyalty: A Global Survey of What Investors Want.” Here, performance ranked number three among both investment pros and clients, with issues of trust, fees, and governance ranked higher.

Originally published on CFA Institute’s Enterprising Investor.

0 Comments